When Rate Cuts Don’t Cut It: The Paradox Explained

Last week, the Federal Reserve delivered its long-awaited rate cut — the first in over a year. Normally, that kind of shift would send long-term yields lower.

Instead, the 10-Year Treasury Yield rose.

At first glance, it’s a paradox. But when you dig into the Fed’s own forecasts, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker, and the housing market’s critical role in the U.S. economy, the move makes sense.

The Fed Cut, but Forecasts Look Steady

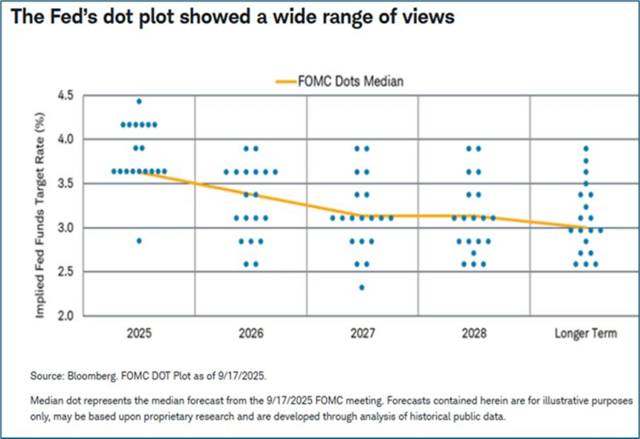

At its September meeting, the Fed cut the Fed funds rate and published an updated dot plot path:

- 2025 Fed funds median: 3.6% (down from 3.9% in June).

- 2026–2027: 3.4% → 3.1%.

- Long run: 3.0%.

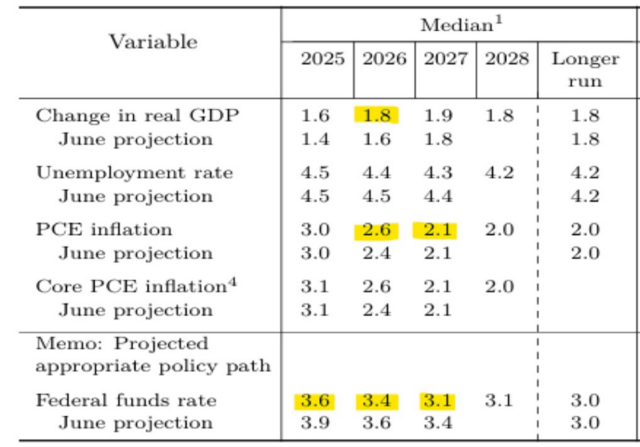

But here’s where the paradox deepens — the Fed’s own forecasts don’t look recessionary:

- GDP growth: 1.6% in 2025, rising to 1.8–1.9% in 2026–27.

- Unemployment: steady at 4.5% in 2025, easing to 4.2% by 2028.

- PCE inflation: 3.0% in 2025, declining gradually to 2.0% by 2028

In other words: The Fed is cutting, but its own outlook suggests an economy that’s still expanding, a labor market that’s stable, and inflation that takes years to return to target.

That’s why the 10-year yield rose instead of falling. Bond investors read the forecasts as confirmation that the Fed isn’t racing back to zero rates. Instead, they see a Fed trying to fine-tune — offering some relief now, but maintaining a “higher for longer” stance to keep inflation anchored.

In fact, the Fed Chair said the following:

“This cut today can be thought of as a risk-management cut, because … we see signs of softening in the labor market … taken together, these signs suggest it’s time to adjust policy toward a more neutral stance.”

What’s a risk management cut? Here’s a little historical context for risk management cuts.

- In 2008, Fed officials often described their pre-crisis cuts as part of a “risk-management approach” — moving early to reduce downside risks.

- In 2019, Powell called his first cut in over a decade a “risk-management cut” in response to trade tensions, framing it as a “mid-cycle adjustment” rather than the start of a deep easing cycle.

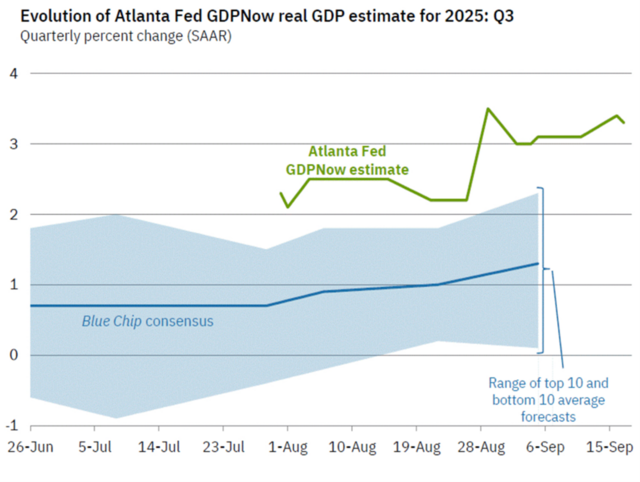

If the Fed’s official forecast seemed steady, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model looked downright strong. As of mid-September, GDPNow pegs Q3 growth near 3%.

That divergence explains why long yields are rising: the real-time economy is running hotter than traditional forecasts imply. Stronger growth means stronger demand, firmer inflation pressure, and a bond market less willing to price in deep rate cuts.

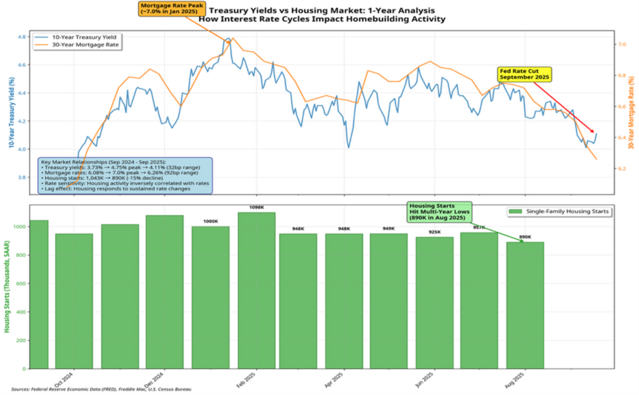

The paradox is clearest in housing — the Fed’s most direct transmission channel:

- Mortgage rates: Peaked at ~7.0% in Jan 2025, now easing to ~6.3% after the cut.

- Housing starts: Fell from 1.04M in late 2024 to just 890K in Aug 2025 (a 15% decline).

- Economic weight: Residential investment makes up 4–5% of GDP directly, but housing-related spending (construction, furniture, appliances, remodeling, commissions) pushes its total footprint closer to 15–18% of GDP.

- Employment: Construction employs over 8M workers, with housing downturns rippling into manufacturing, retail, and local tax revenues.

This is why the Fed is cutting: not because growth is collapsing, but because housing — a cornerstone of the economy — is flashing stress signals.

So here’s the paradox in plain English:

- The Fed is cutting rates.

- But its own forecasts show an economy that doesn’t need rescuing — growth is steady, jobs are stable, and inflation only drifts down slowly.

- GDPNow says growth may even be running hotter than consensus.

- Housing, though, is softening enough to justify caution.

The 10-year yield rose because the bond market is looking through the cut: investors see resilience, not recession, and sticky inflation, not collapse.

The Fed’s first cut in over a year wasn’t about a collapsing economy — it was about preventing housing from becoming a drag that spills into everything else. But the bond market is telling us the bigger picture: until inflation convincingly moves lower and housing stabilizes, yields will stay firm.

The paradox is real: a Fed easing policy in the short run, while forecasting an economy strong enough to resist a full easing cycle. And that’s why the rate cut didn’t cut it.

If you have questions or comments, please let us know. You can contact us via X and Facebook, or you can e-mail Tim directly. For additional information, please visit our website.

Tim Phillips, CEO, Phillips & Company

Sources:

The charts and data presented are sourced from a combination of public domain materials and licensed data providers. Their use is intended solely for educational and analytical commentary and falls within the scope of fair use. For a representative list of sources, please click here.

The material contained within (including any attachments or links) is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice, nor should it be considered as a recommendation, offer, or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security, or to adopt a specific investment strategy. The information contained herein is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy or completeness is not guaranteed. All opinions expressed are subject to change without notice. Investment decisions should be made based on an investor’s objective.