Who Counts in a Crisis?

This week we will hear the scholars and PhDs of the Federal Reserve pontificate at their annual retreat in Jackson Hole. The topic will likely center around Federal Reserve independence and the ruling elite. What I hope they talk about is who counts in a crisis.

The U.S. economy looks strong at the surface level. Growth is steady and aggregate consumer spending continues to support GDP. But the headline strength hides a painful truth: the benefits are unevenly distributed. Higher-income households are powering through, while lower-income Americans are being squeezed harder than ever.

This imbalance raises a fundamental question for policymakers: if the economy can’t work for everyone, then who really counts in a crisis?

When Higher Rates Hit the Lowest Incomes Hardest

The Federal Reserve’s higher-for-longer stance has come at a steep cost for the bottom half of the income spectrum:

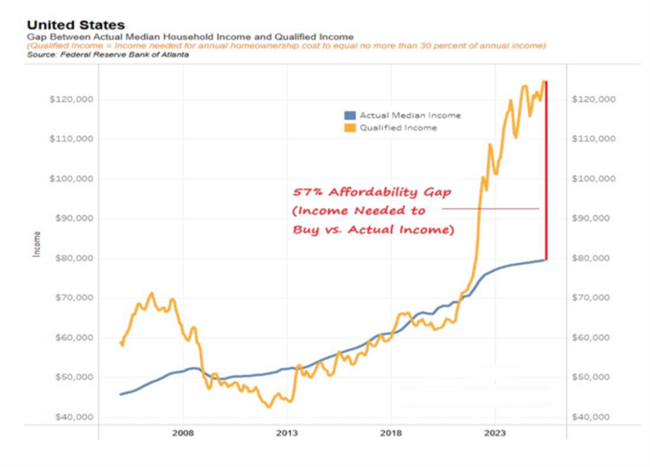

- Housing affordability has collapsed. It now takes more than $120,000 in qualified income to buy a median home, compared to a median household income of ~$80,000—a 57% gap.

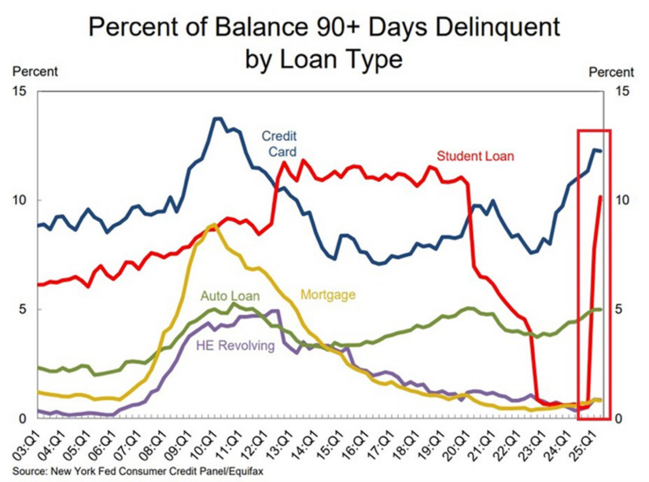

- Debt stress is mounting. Delinquency rates are climbing, and student loan repayments have resumed, weighing on younger borrowers in particular.

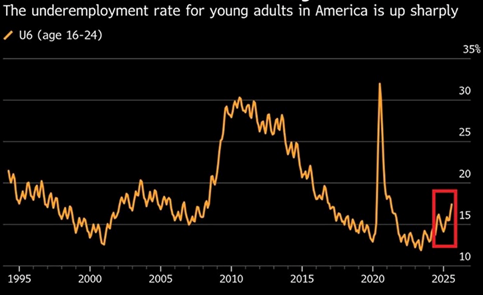

- Job fragility is rising. Underemployment among young adults (ages 16–24) has surged to nearly 15%, reflecting weaker job quality and reduced opportunity.

For wealthier households, higher rates mean higher savings yields. For lower-income households, they mean exclusion, stress, and declining economic mobility.

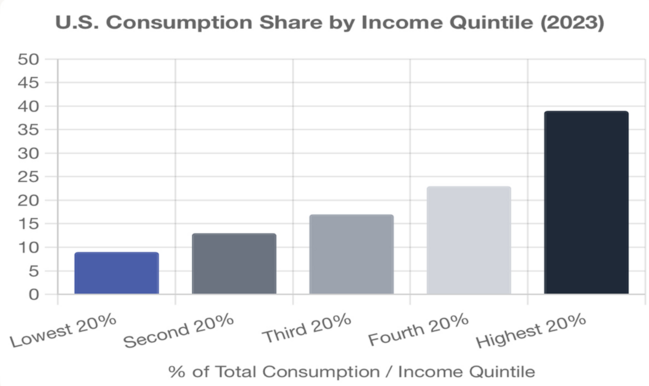

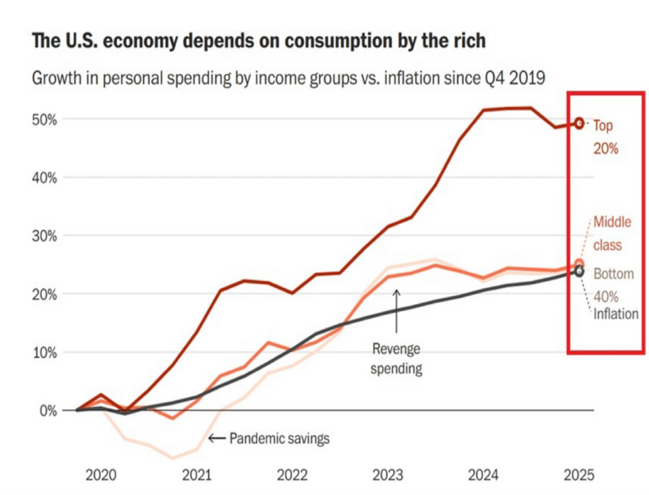

The structure of U.S. consumption highlights this divide.

- The top 20% of households account for nearly 40% of consumption.

- Since 2020, their spending has surged by nearly 50%. Meanwhile, the bottom 40% has barely kept pace with inflation.

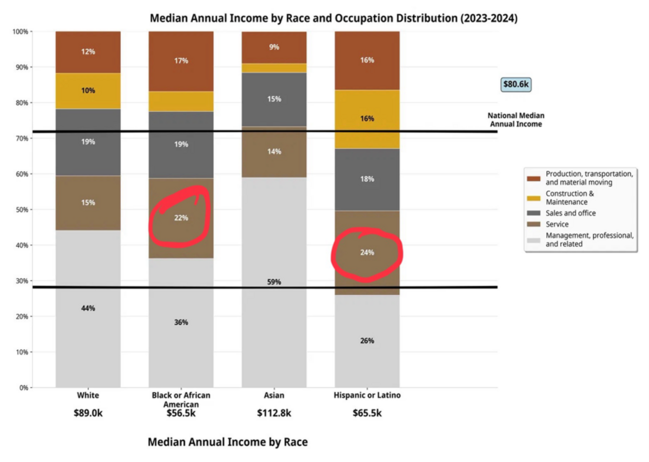

Black and Hispanic workers are disproportionately concentrated in service occupations—roles that tend to be lower paid and more vulnerable to shocks. Median incomes of $40,200 for Black households and $35,600 for Hispanic households are far below the national median, magnifying the effect of higher rates.

The result is a barbell economy: robust spending at the top, fragile conditions at the bottom.

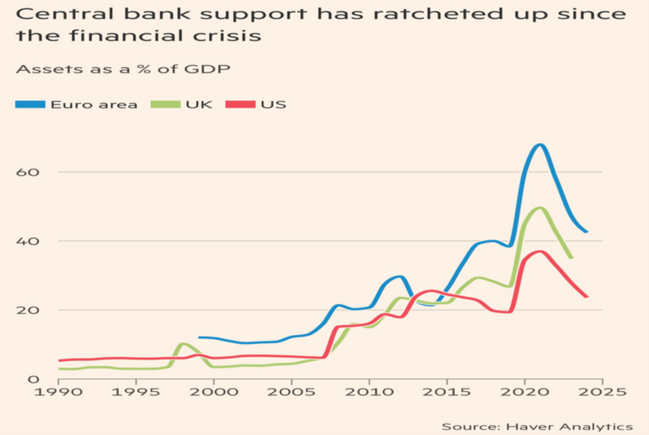

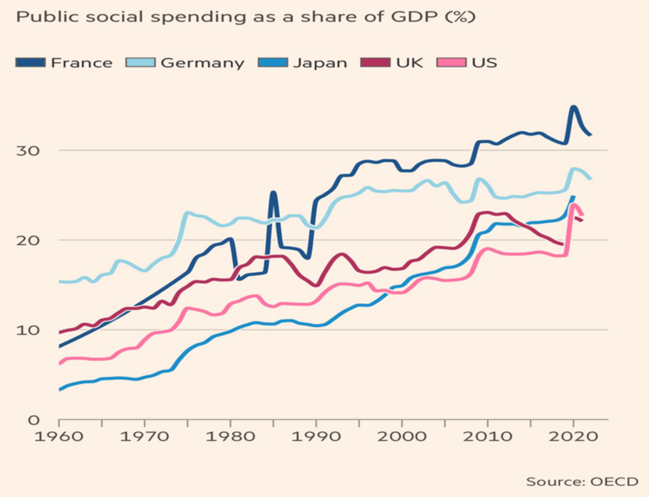

For the past 15 years, policy interventions have repeatedly cushioned the consumer.

- Central banks expanded balance sheets to unprecedented levels during the financial crisis and the pandemic.

- Public social spending in the U.S. has risen to over 20% of GDP in the United States.

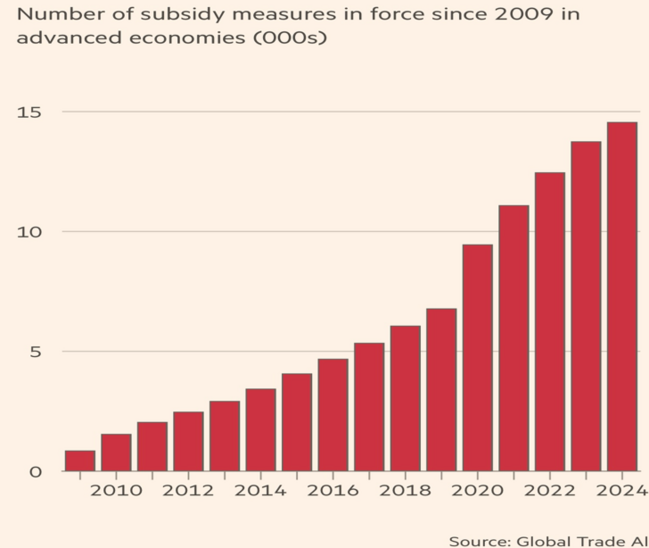

- Subsidy measures in advanced economies have exploded, multiplying more than fivefold since 2009.

These interventions kept lower income households afloat. But now, the very cohorts who benefited most are being hammered by higher borrowing costs. You cannot use subsidies and stimulus to bail out the consumer for over a decade, then turn around and squeeze them with restrictive policy.

Why might rate cuts happen no matter what inflation does in the next month?

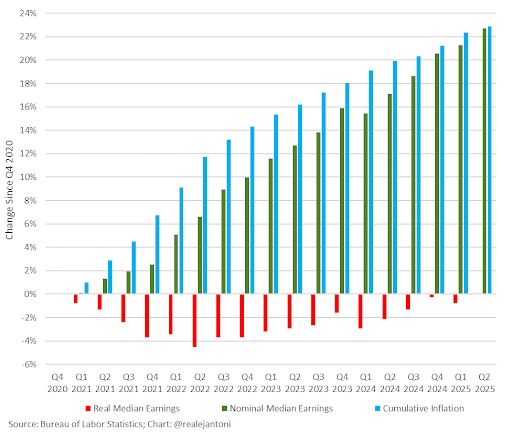

For the first time in years, real wages have turned positive—a fragile but important milestone. But that progress risks being undone if high rates persist.

The case for cuts is not just about growth. It’s about balance.

- Relief for lower-income households would sustain broader participation in the economy.

- Failure to ease risks further entrenching a two-speed system where only the top thrives.

Who Counts in a Crisis?

The U.S. economy is strong, but not for everyone. The wealthy are resilient; the poor are struggling. Rates are biting at the bottom just as real wages begin to recover.

So, this week, when should be hearing about the Federal Reserve’s stance on an economy for everyone, I fear we are going to hear a bunch of Fed speak on their own independence. If they don’t start helping the lower income cohorts, the pain could soon spill over into the middle income folks.

And so, the question hangs in the air: when policymakers make their choices, who really counts in a crisis?

If you have questions or comments, please let us know. You can contact us via X and Facebook, or you can e-mail Tim directly. For additional information, please visit our website.

Tim Phillips, CEO, Phillips & Company

Sources:

The charts and data presented are sourced from a combination of public domain materials and licensed data providers. Their use is intended solely for educational and analytical commentary and falls within the scope of fair use. For a representative list of sources, please click here.

The material contained within (including any attachments or links) is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice, nor should it be considered as a recommendation, offer, or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security, or to adopt a specific investment strategy. The information contained herein is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy or completeness is not guaranteed. All opinions expressed are subject to change without notice. Investment decisions should be made based on an investor’s objective.